A Proposed Framework for Root Cause Analysis

Published April 25, 2023

CQEC Development Team: Ben Dupslaff, Steve Solloway, Steve Worner, Steve Black, Collin Sutt, Scott Staffon, Scott West

Introduction

Organizations must implement a simple problem-solving methodology which facilitates root cause analysis (RCA) within the context of the business, resisting the urge to haphazardly concentrate resources on a failing process – hoping it will be improved. What follows is a flexible framework for establishing an effective root cause analysis system that an organization and its project teams can use to drive and sustain process improvement.

Create a "Process Enterprise" Organizational View

Many architectural / engineering and construction organizations pride themselves on superior problem solving – their cultures pushing for quick resolutions. This culture is a natural result of cost and schedule pressures faced by project teams. Though not wrong, this environment allows overly confident opinions and dualistic thinking to flourish, pushing managers to find quick solutions before confirming they are solving the right problem or understanding the root cause (Wedell-Wedellsborg). Or, if the right problem is identified, a haphazard approach to problem solving prevents it from being fully resolved and the knowledge transferred to prevent future issues. Being too quick to jump in and solve a problem versus the problem impacts an organization’s agility and competitiveness.

Because the basis of root cause analysis is process, a “process enterprise” view is required before quality incidents can be identified, resolved and corresponding processes improved. A “process enterprise” is an organization that focuses on horizontal business processes which overlay and integrate its vertical business unit structure (Hammer and Stanton). When individual employees use integrated processes, they visualize how their work efforts promote the business strategy. In a “process enterprise,” business units are forced to collaborate, promoting an open culture where communication of learning is routine, expected and celebrated by top leadership.

When success of a process has higher priority than individual business unit profit and loss, the organization’s culture is ready for implementing a root cause analysis methodology.

Promote Open Communication Habits at the Project Level

A “root cause” is the incident which creates a defect. Incidents are often the result of honest mistakes and human error which can be uncomfortable to share, especially on a construction project team. When corporate leaders come in to investigate, the project team’s defenses go up and there’s natural hesitation to share incidents. Corporate visibility into quality incidents will not occur until the culture of the project team allows for open discussion of incidents. If a project team member is not comfortable sharing an issue with their coworkers, they won't share incidents with corporate leaders for analysis regardless of the learning and improvement opportunities.

Leaders need to define what open communication is and establish a means of open communication at the project level prior to setting up a corporate incident reporting system. Project teams need to be comfortable talking about incidents, learning how to do it objectively without blame with leaders in the room. This helps promote early visibility of incidents and creates a safe environment for corporate reporting to occur.

Though it may appear and feel rigid at first, leaders must facilitate new communication habits for information to start flowing. Below is a suggested framework:

1. Identify a regular project meeting where “learning discussions” occur, such as a monthly risk or controls meeting.

2. Coach project teams prior to the meeting of what to expect.

- What type of feedback leaders may be looking for.

- What is the goal of sharing what incidents occurred?

- That the discussion is a safe place with no judgment.

- Provide examples of what to share:

* Lack of training for an installing craft worker

* Improper material delivered to the project site

* Missed inspection due to staffing

3. Ask one of the more influential and experienced project team leaders to share first.

4. Listen, think critically, and ask questions about the process that may have failed - not the people.

5. Inform the team specifically what the organization will do with the information to improve.

6. Show how the teams will benefit from the knowledge sharing.

7. Reward the team for sharing.

The goal is to create a habit of reporting incidents immediately. Project teams need to be guided there slowly over time – especially if this is completely new to the organization. The consistency of regularly talking about incidents will create additional cultural momentum toward improvement. Leaders should continue to facilitate these discussions until new habits are formed, focusing on process and fixing what went wrong – not placing blame.

Set Graded Thresholds for Action

When an incident occurs – such as unauthorized product substitutions or finishes not properly cured – organizations and their project teams need to know what to do with it.

The common seven step process for root cause analysis is noted below:

1. Identify the problem and the process (using tools below which best fit the organization):

- Brainstorming

- Five Whys

- Pareto Chart

- Scatter Diagram

- Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagram

2. List possible root causes.

3. Search out the most likely root cause.

4. Identify potential solutions.

5. Select and implement a solution.

6. Follow up to evaluate the effect.

7. Standardize the process.

When viewing the organization as a collection of horizontal processes, incidents can be prioritized in accordance with their severity and risk potential. Depending on the severity of the incident, project teams may not have capacity to conduct an in-depth study using the above process. Establishing thresholds for action is an effective way to coach project teams on what to do when an incident occurs. Without established thresholds, energy expended on root cause analysis will be either too little or not enough[1] [2]. Teams must know that a full-scale root cause analysis is not appropriate for every event.

We recommend a simple hierarchy of Low, Medium, and High – where management specifies the differentiators between each within the context of their business strategy. This will vary based on experience and tolerance for recurring issues as well as cost, schedule, customer relationships, and reputation. There may be a different threshold or criteria for each incident type.

Low (or minor) incidents may be immediately identified and resolved by local project teams without going through the seven steps, requiring little, if any, overhead effort from corporate resources. Project teams can immediately implement changes as necessary to prevent similar incidents from occurring locally at the same project. Thresholds for Low impact incidents may include rework costs less than $25,000 or schedule impacts less than two days.

Medium and High impact incidents will require many more resources to identify the root cause. For High impact incidents – examples include critical path delay, significant financial implications or damage to client relationships and organization reputation – a more thorough review of the seven steps is required. This is when the organization needs separate corporate resources to act quickly while the facts are truly discoverable. As time passes, it is more difficult to distinguish between truth and collective “agreement” on what went wrong. There may also be more than one root cause.

An exception to Low and Medium incidents are trends of similar issues within those thresholds. Recurring issue frequency can be another threshold to identify the need for root cause analysis. A repeating Minor incident is a significant drain in resources. The same corporate resources that support root cause analysis for High impact incidents can also help project teams recognize when trends are occurring, given their visibility at the enterprise level.

For additional information on setting thresholds and measuring incident severity and frequency, reference the CQEC’s publication on “Measuring Quality in Construction.”

Establish a Low Friction Reporting, Categorization, and Analysis Method

After teams get into the habit of talking about incidents and resolving Minor incidents locally, their thinking will shift from “How does this impact me?” to “How would this impact someone else?” This is where a culture of reporting begins.

Reporting creates visibility and awareness of quality incidents. Like safety, a culture of reporting is fostered when there’s a cultural focus on process. In a fully mature quality program, project staff routinely report all undesired outcomes from bent door frames, failed tests, or the wrong material delivered to the project site.

The method of reporting is just as critical as the culture. For true organizational awareness of incidents, the reporting method needs to be simple and accessible for project teams. Many organizations implement detailed forms which feed databases to build lessons learned insights. Teams worry about filling out cells correctly, which reduces reporting participation. Forms become “one more thing” project teams need to complete.

We suggest shifting the filtering and categorization of incidents from the project teams to the corporate quality function. This allows project teams to focus on sharing the information rather than not reporting due to concerns they may categorize the incident incorrectly. To form a new habit of reporting, friction needs to be low in the method. The reporting method can be any available software or technology that fits the needs of the organization. The process must be developed first before selecting the reporting tool. Pick the tool that meets the need rather than building a process around the tool.

In these early stages of reporting, the organization should be focused on creating visibility around quality incidents. Get the information flowing. If a company is not aware of incidents, there is no chance to identify the root cause and eliminate them.

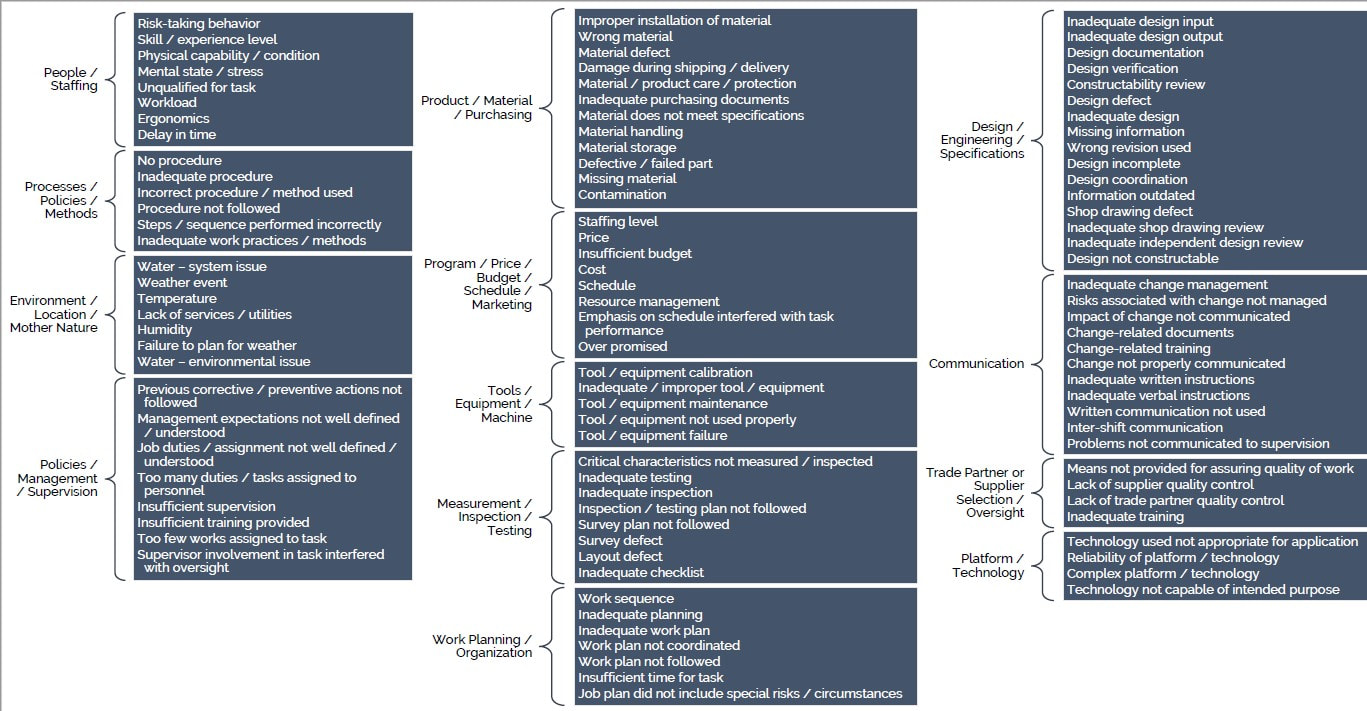

Once incidents become visible, the corporate quality function can begin categorizing the incidents. Categorizing types of incidents is part of the transformation to becoming a learning organization. Without culture, communication, and thresholds for action, an organization has no idea what kinds of incidents are creating inefficiencies in operations. Below is a baseline set of categories an organization may start with.

These categories can be expanded to get a deeper understanding of what processes need to be improved.

Organizations must implement a simple problem-solving methodology which facilitates root cause analysis (RCA) within the context of the business, resisting the urge to haphazardly concentrate resources on a failing process – hoping it will be improved. What follows is a flexible framework for establishing an effective root cause analysis system that an organization and its project teams can use to drive and sustain process improvement.

Create a "Process Enterprise" Organizational View

Many architectural / engineering and construction organizations pride themselves on superior problem solving – their cultures pushing for quick resolutions. This culture is a natural result of cost and schedule pressures faced by project teams. Though not wrong, this environment allows overly confident opinions and dualistic thinking to flourish, pushing managers to find quick solutions before confirming they are solving the right problem or understanding the root cause (Wedell-Wedellsborg). Or, if the right problem is identified, a haphazard approach to problem solving prevents it from being fully resolved and the knowledge transferred to prevent future issues. Being too quick to jump in and solve a problem versus the problem impacts an organization’s agility and competitiveness.

Because the basis of root cause analysis is process, a “process enterprise” view is required before quality incidents can be identified, resolved and corresponding processes improved. A “process enterprise” is an organization that focuses on horizontal business processes which overlay and integrate its vertical business unit structure (Hammer and Stanton). When individual employees use integrated processes, they visualize how their work efforts promote the business strategy. In a “process enterprise,” business units are forced to collaborate, promoting an open culture where communication of learning is routine, expected and celebrated by top leadership.

When success of a process has higher priority than individual business unit profit and loss, the organization’s culture is ready for implementing a root cause analysis methodology.

Promote Open Communication Habits at the Project Level

A “root cause” is the incident which creates a defect. Incidents are often the result of honest mistakes and human error which can be uncomfortable to share, especially on a construction project team. When corporate leaders come in to investigate, the project team’s defenses go up and there’s natural hesitation to share incidents. Corporate visibility into quality incidents will not occur until the culture of the project team allows for open discussion of incidents. If a project team member is not comfortable sharing an issue with their coworkers, they won't share incidents with corporate leaders for analysis regardless of the learning and improvement opportunities.

Leaders need to define what open communication is and establish a means of open communication at the project level prior to setting up a corporate incident reporting system. Project teams need to be comfortable talking about incidents, learning how to do it objectively without blame with leaders in the room. This helps promote early visibility of incidents and creates a safe environment for corporate reporting to occur.

Though it may appear and feel rigid at first, leaders must facilitate new communication habits for information to start flowing. Below is a suggested framework:

1. Identify a regular project meeting where “learning discussions” occur, such as a monthly risk or controls meeting.

2. Coach project teams prior to the meeting of what to expect.

- What type of feedback leaders may be looking for.

- What is the goal of sharing what incidents occurred?

- That the discussion is a safe place with no judgment.

- Provide examples of what to share:

* Lack of training for an installing craft worker

* Improper material delivered to the project site

* Missed inspection due to staffing

3. Ask one of the more influential and experienced project team leaders to share first.

4. Listen, think critically, and ask questions about the process that may have failed - not the people.

5. Inform the team specifically what the organization will do with the information to improve.

6. Show how the teams will benefit from the knowledge sharing.

7. Reward the team for sharing.

The goal is to create a habit of reporting incidents immediately. Project teams need to be guided there slowly over time – especially if this is completely new to the organization. The consistency of regularly talking about incidents will create additional cultural momentum toward improvement. Leaders should continue to facilitate these discussions until new habits are formed, focusing on process and fixing what went wrong – not placing blame.

Set Graded Thresholds for Action

When an incident occurs – such as unauthorized product substitutions or finishes not properly cured – organizations and their project teams need to know what to do with it.

The common seven step process for root cause analysis is noted below:

1. Identify the problem and the process (using tools below which best fit the organization):

- Brainstorming

- Five Whys

- Pareto Chart

- Scatter Diagram

- Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagram

2. List possible root causes.

3. Search out the most likely root cause.

4. Identify potential solutions.

5. Select and implement a solution.

6. Follow up to evaluate the effect.

7. Standardize the process.

When viewing the organization as a collection of horizontal processes, incidents can be prioritized in accordance with their severity and risk potential. Depending on the severity of the incident, project teams may not have capacity to conduct an in-depth study using the above process. Establishing thresholds for action is an effective way to coach project teams on what to do when an incident occurs. Without established thresholds, energy expended on root cause analysis will be either too little or not enough[1] [2]. Teams must know that a full-scale root cause analysis is not appropriate for every event.

We recommend a simple hierarchy of Low, Medium, and High – where management specifies the differentiators between each within the context of their business strategy. This will vary based on experience and tolerance for recurring issues as well as cost, schedule, customer relationships, and reputation. There may be a different threshold or criteria for each incident type.

Low (or minor) incidents may be immediately identified and resolved by local project teams without going through the seven steps, requiring little, if any, overhead effort from corporate resources. Project teams can immediately implement changes as necessary to prevent similar incidents from occurring locally at the same project. Thresholds for Low impact incidents may include rework costs less than $25,000 or schedule impacts less than two days.

Medium and High impact incidents will require many more resources to identify the root cause. For High impact incidents – examples include critical path delay, significant financial implications or damage to client relationships and organization reputation – a more thorough review of the seven steps is required. This is when the organization needs separate corporate resources to act quickly while the facts are truly discoverable. As time passes, it is more difficult to distinguish between truth and collective “agreement” on what went wrong. There may also be more than one root cause.

An exception to Low and Medium incidents are trends of similar issues within those thresholds. Recurring issue frequency can be another threshold to identify the need for root cause analysis. A repeating Minor incident is a significant drain in resources. The same corporate resources that support root cause analysis for High impact incidents can also help project teams recognize when trends are occurring, given their visibility at the enterprise level.

For additional information on setting thresholds and measuring incident severity and frequency, reference the CQEC’s publication on “Measuring Quality in Construction.”

Establish a Low Friction Reporting, Categorization, and Analysis Method

After teams get into the habit of talking about incidents and resolving Minor incidents locally, their thinking will shift from “How does this impact me?” to “How would this impact someone else?” This is where a culture of reporting begins.

Reporting creates visibility and awareness of quality incidents. Like safety, a culture of reporting is fostered when there’s a cultural focus on process. In a fully mature quality program, project staff routinely report all undesired outcomes from bent door frames, failed tests, or the wrong material delivered to the project site.

The method of reporting is just as critical as the culture. For true organizational awareness of incidents, the reporting method needs to be simple and accessible for project teams. Many organizations implement detailed forms which feed databases to build lessons learned insights. Teams worry about filling out cells correctly, which reduces reporting participation. Forms become “one more thing” project teams need to complete.

We suggest shifting the filtering and categorization of incidents from the project teams to the corporate quality function. This allows project teams to focus on sharing the information rather than not reporting due to concerns they may categorize the incident incorrectly. To form a new habit of reporting, friction needs to be low in the method. The reporting method can be any available software or technology that fits the needs of the organization. The process must be developed first before selecting the reporting tool. Pick the tool that meets the need rather than building a process around the tool.

In these early stages of reporting, the organization should be focused on creating visibility around quality incidents. Get the information flowing. If a company is not aware of incidents, there is no chance to identify the root cause and eliminate them.

Once incidents become visible, the corporate quality function can begin categorizing the incidents. Categorizing types of incidents is part of the transformation to becoming a learning organization. Without culture, communication, and thresholds for action, an organization has no idea what kinds of incidents are creating inefficiencies in operations. Below is a baseline set of categories an organization may start with.

- People/Staffing

- Policies/Management/Supervision

- Tools/Equipment/Machine

- Process/Practice/Method

- Product/Material/Purchasing

- Design/Engineering/Specifications

- Measurement/Inspection/Testing

- Partner/Supplier Selection and Oversight

- Place/Environment/Mother Nature

- Program/Price/Budget/Schedule/Marketing

- Work Planning/Organization/Communication

These categories can be expanded to get a deeper understanding of what processes need to be improved.

Depending on the organization, root cause analysis categories and subcategories could become extensive. Another common resource is the Kepner-Tregoe 6M (materials, personnel, methods, machines, environment, measures) where historically personnel is “man” and environment is “milieu” (Kepner and Tregoe). When looking for the root cause, Kepner-Tregoe also note that nearly all quality-problems most fall into following five categories (Tregoe and Kepner):

As additional visibility is created around quality incidents, an organization will experience and understand what risks areas are prevalent. It may be necessary to refine the categories to add additional levels of detail such as the listing above.

Transfer Knowledge by Integrating Resolutions into Workflows

Timing and method are key elements for knowledge transfer. For tacit and explicit knowledge, there are three areas to address:

With easy access to data and dashboards, many organizations create searchable databases of their lessons learned. This can be a great tool for initiating a transparent and open culture. However, the risk is that knowledge in the database isn’t timely. If the knowledge is something the workforce doesn’t know it doesn’t know (Item 3 above), then they won’t know when to search the database or what to search for.

Mapping incident timing relative to a typical project schedule will resolve the concern of what knowledge to share with the project team and when. This visual also helps achieve leadership buy-in on where the organization's process improvement efforts will be focused.

Knowledge needs to be transferred as part of the workflow at a time in the project where the resolution is most relevant to the risk it will prevent. Resolutions need to be easy to digest and part of work plans and instructions. An example for a design firm could be updating a detail within a detail library to prevent recurring constructability issues in future drawing sets. When the new detail is utilized, the knowledge and incident resolution are already in the workflow – the designer may be unaware they are utilizing a resolution to a quality incident. This approach doesn’t require teams to search a database at the beginning of a project for every potential incident that may occur. It also focuses resources on the right things at the right time.

Another effective example is inserting lessons learned into work planning activities. Impactful work planning and project estimating are points in time when the project and estimating teams can be compelled to seek out lessons learned from a convenient database or process and integrate the knowledge into their actions in the field and estimate.

Integrate Preventative Focus Areas into Business Planning

An organization must progress from reactive to preventative. The creation of culture, process and habits must happen first in reaction to incidents to learn what to prevent before becoming preventative. Just as an organization may solve the wrong problems by jumping to conclusions, preventing the wrong or nonexistent issue relative to other incidents could also occur, expending unnecessary overhead in doing so.

This is what becoming a learning organization means: transferring knowledge effectively to prevent recurring incidents. Where might a quality incident occur on a similar type of construction? What risks are coming that need to be mitigated? This is where Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) becomes useful: utilizing root cause analysis leanings on preventative basis to avoid past incidents on projects in the design and planning state.

Using established categories, leadership informs project teams where and when to focus their available energy. This helps local project teams understand the state of the organization and potential risks to avoid. Focus areas can be determined each quarter or year in conjunction with regular business planning and strategy to mitigate the most impactful incidents. As losses in each focus category decrease, this validates the organization's RCA efforts.

Review of the Proposed Framework

Using the basic seven steps of root cause analysis alone won’t work without the right culture, communication, thresholds for action, reporting methods and integration with business planning. The framework below creates a culture and environment for root cause analysis to occur methodically. Each of the steps in the framework can only be executed by senior and executive leadership.

This is an interactive process, focusing on small improvements over time. Each step can’t be implemented at the same time as the organization only has so much capacity for change and initiative rollout. This entire framework can’t be rolled out in 6 months. It may take 12 to 18 or more, depending on the organization’s size and complexity. Too much knowledge transfer from one source has a low rate of information transfer, making implementation and process improvement take too long and decrease in its effectiveness.

Within a process enterprise, process owners can leverage this framework to continuously improve processes for the entire organization. As incident data comes in, process owners can push for small wins, generating momentum and support. They can share data with all functional business units utilizing integrated processes, from preconstruction to operations.

Defining and Measuring Success

Root cause analysis drives measurable continuous improvement and becomes sustainable when the organization’s culture supports and celebrates learning. When this framework is successfully implemented, the following occurs within the organization:

Closing Thoughts

Continuous improvement through root cause analysis is sustainable within an intentionally open culture where there is no fear of reprisal and discussion of quality incidents is encouraged. A quality program is incomplete without a standard method for root cause analysis which fits the organization's strategy. An organization needs its own model of root cause analysis specific to the context and culture of the organization which guides it through process improvement – root cause analysis being the organization’s custom framework for continuous improvement.

Works Cited

- Conformance

- Efficiency

- Unstructured Performance

- Product Design

- Process Design

As additional visibility is created around quality incidents, an organization will experience and understand what risks areas are prevalent. It may be necessary to refine the categories to add additional levels of detail such as the listing above.

Transfer Knowledge by Integrating Resolutions into Workflows

Timing and method are key elements for knowledge transfer. For tacit and explicit knowledge, there are three areas to address:

- What does the workforce know?

- What does the workforce know that it does not know?

- What does the workforce not know that it does not know?

With easy access to data and dashboards, many organizations create searchable databases of their lessons learned. This can be a great tool for initiating a transparent and open culture. However, the risk is that knowledge in the database isn’t timely. If the knowledge is something the workforce doesn’t know it doesn’t know (Item 3 above), then they won’t know when to search the database or what to search for.

Mapping incident timing relative to a typical project schedule will resolve the concern of what knowledge to share with the project team and when. This visual also helps achieve leadership buy-in on where the organization's process improvement efforts will be focused.

Knowledge needs to be transferred as part of the workflow at a time in the project where the resolution is most relevant to the risk it will prevent. Resolutions need to be easy to digest and part of work plans and instructions. An example for a design firm could be updating a detail within a detail library to prevent recurring constructability issues in future drawing sets. When the new detail is utilized, the knowledge and incident resolution are already in the workflow – the designer may be unaware they are utilizing a resolution to a quality incident. This approach doesn’t require teams to search a database at the beginning of a project for every potential incident that may occur. It also focuses resources on the right things at the right time.

Another effective example is inserting lessons learned into work planning activities. Impactful work planning and project estimating are points in time when the project and estimating teams can be compelled to seek out lessons learned from a convenient database or process and integrate the knowledge into their actions in the field and estimate.

Integrate Preventative Focus Areas into Business Planning

An organization must progress from reactive to preventative. The creation of culture, process and habits must happen first in reaction to incidents to learn what to prevent before becoming preventative. Just as an organization may solve the wrong problems by jumping to conclusions, preventing the wrong or nonexistent issue relative to other incidents could also occur, expending unnecessary overhead in doing so.

This is what becoming a learning organization means: transferring knowledge effectively to prevent recurring incidents. Where might a quality incident occur on a similar type of construction? What risks are coming that need to be mitigated? This is where Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) becomes useful: utilizing root cause analysis leanings on preventative basis to avoid past incidents on projects in the design and planning state.

Using established categories, leadership informs project teams where and when to focus their available energy. This helps local project teams understand the state of the organization and potential risks to avoid. Focus areas can be determined each quarter or year in conjunction with regular business planning and strategy to mitigate the most impactful incidents. As losses in each focus category decrease, this validates the organization's RCA efforts.

Review of the Proposed Framework

Using the basic seven steps of root cause analysis alone won’t work without the right culture, communication, thresholds for action, reporting methods and integration with business planning. The framework below creates a culture and environment for root cause analysis to occur methodically. Each of the steps in the framework can only be executed by senior and executive leadership.

- Create a “Process Enterprise” Organizational View

- Promote Open Communication Habits at the Project Level

- Set Graded Thresholds for Action

- Establish a Low Friction Reporting, Categorizing, and Analysis Method

- Transfer Knowledge by Integrating Resolutions into Workflows

- Integrate Preventative Focus Areas into Business Planning

This is an interactive process, focusing on small improvements over time. Each step can’t be implemented at the same time as the organization only has so much capacity for change and initiative rollout. This entire framework can’t be rolled out in 6 months. It may take 12 to 18 or more, depending on the organization’s size and complexity. Too much knowledge transfer from one source has a low rate of information transfer, making implementation and process improvement take too long and decrease in its effectiveness.

Within a process enterprise, process owners can leverage this framework to continuously improve processes for the entire organization. As incident data comes in, process owners can push for small wins, generating momentum and support. They can share data with all functional business units utilizing integrated processes, from preconstruction to operations.

Defining and Measuring Success

Root cause analysis drives measurable continuous improvement and becomes sustainable when the organization’s culture supports and celebrates learning. When this framework is successfully implemented, the following occurs within the organization:

- Project teams habitually communicate incidents, defining and resolving root causes for Low impact events.

- Corporate resources identify and resolve Medium and High impact root causes.

- Resolutions are built into processes and workflows, transferring the right knowledge when it's needed.

- Leaders use incident data to pick the highest risk areas to incorporate resolutions into their business strategy.

- Process utilization increases as teams find the root cause analysis process easy to use and beneficial to their work.

Closing Thoughts

Continuous improvement through root cause analysis is sustainable within an intentionally open culture where there is no fear of reprisal and discussion of quality incidents is encouraged. A quality program is incomplete without a standard method for root cause analysis which fits the organization's strategy. An organization needs its own model of root cause analysis specific to the context and culture of the organization which guides it through process improvement – root cause analysis being the organization’s custom framework for continuous improvement.

Works Cited

- Hammer, Michael, and Steven Stanton. “How Process Enterprises Really Work.” Harvard Business Review, no. November 1999.

- Kepner, Charles, and Ben Tregoe. Problem Analysis and Decision Making. Princeton, NJ, Princeton Research Press, 1979.

- Tregoe, Ben, and Charles Kepner. The Rational Manager. New York, NY, McGraw Hill, 1965.

- Wedell-Wedellsborg, Thomas. “Are You Solving the Right Problems?” Harvard Business Review, vol. January 2017.

The Construction Quality Executives Council (CQEC) is an industry organization composed of Quality Leaders from design and construction firms with formal Quality Programs. The goal of the CQEC is to advance the art and science of quality in the built environment through publications, education and research. The information and views expressed in this document is that of the CQEC and not that of the member’s company. This document is copyrighted (2018©) and the CQEC grants permission to reproduce and distribute as long as credit to the source document and CQEC is maintained.